The results of recent research suggests that ancient, or pre-historic, builders of the monumental structures found in such diverse places as Ireland, Malta, southern Turkey and Peru all have a peculiarly common characteristic – they may have been specially designed to conduct and manipulate sound to produce certain sensory effects.

Some ancient monumental structures were built to manipulate sound for sensory and mind effects – suggests recent research.

Beginning in 2008, a recent and on-going study of the massive 6,000 year-old stone structure complex known as the “Hal Saflieni Hypogeum“ on the island of Malta, for example, is producing some revelatory results.

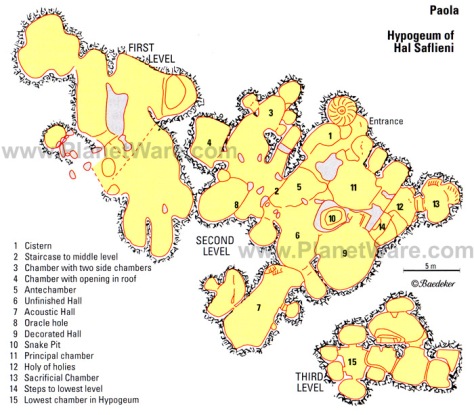

The Hypogeum of Hal Saflieni is an underground cave system covering around 500m² on 3 levels, with various inter-connecting corridors and passage ways that lead to a number of small chambers, built between 3000-2500 B.C. The cave system was re-discovered in 1902 and since then there has been particular interest in one of the rooms, named the “Oracle Chamber”. The space is said to amplify voices dramatically, with certain frequencies resonating enough to be felt through the body. But this structure is unique in that it is subterranean.

As knowledge of this phenomenon has spread, many investigations have been carried out into its acoustic properties as well as other similarly designed spaces across the world.

Low voices within its walls create eerie, reverberating echoes, and a sound made or words spoken in certain places can be clearly heard throughout all of its three levels. Now, scientists are suggesting that certain sound vibration frequencies created when sound is emitted within its walls are actually altering human brain functions of those within earshot.

Research has shown that a number of these locations (such as that at Newgrange, Ireland) have very similar acoustic features, specifically resonating at 110Hz.

It is still not known whether the space was specifically designed to produce these resonances (which would indicate a very early understanding of acoustics and sound) or if it was simply a lucky coincidence with those particular room dimensions and rock type. The use of the space is also unknown, was it a ritual site where chanting and singing were common, or maybe a temple for prayer?

Research carried out in February 2014 by Dr. Paolo Debertolis, Department of Medical Sciences, University of Trieste, Italy and Linda C. Eneix, Mediterranean Institute of Ancient Civilizations, may shed some light on the use of the space by investigating the type of noise sources that are capable of exciting the resonances of the space.

Regional brain activity in a number of healthy volunteers was monitored by EEG through exposure to different sound vibration frequencies. The findings indicated that at 110Hz the patterns of activity over the pre-frontal cortex abruptly shifted, resulting in a relative de-activation of the language center and a temporary shifting from left to right-sided dominance related to emotional processing and creativity. This shifting did not occur at 90Hz or 130Hz. In addition to stimulating their more creative sides, it appears that an atmosphere of resonant sound in the frequency of 110Hz or 111Hz would have been “switching on” an area of the brain that bio-behavioral scientists believe relates to mood, empathy and social behavior. Deliberately or not, the people who spent time in such an environment under conditions that may have included a low male voice – in ritual chanting or even simple communication – were exposing themselves to vibrations that may have actually impacted their thinking.

Researchers at the University of Malta are confirming the findings in an on-going study.

But the Hypogeum is not alone in its peculiar sound effects. A study conducted in 1994 by a consortium from Princeton University found that acoustic behavior in ancient chambers at megalithic sites such as Newgrange in Ireland and Wayland’s Smithy in England was characterized by a strong sustained resonance, or “standing wave” in a frequency range between 90Hz and 120Hz. “When this happens”, says Eneix, “what we hear becomes distorted, eerie. The exact pitch for this behavior varies with the dimensions of the room and the quality of the stone.” Going further back in time, she points to the ancient 10,000 B.C. site of “Göbekli Tepe” in southern Turkey. Located on a hilltop, it consists of 20 round stone-built structures which had been buried. Those structures that have been excavated feature massive, T-shaped, standing limestone pillars. “In the center of a circular shrine,” she says, “a limestone pillar “sings” when smacked with the flat of the hand.”

And now, new findings of a recent archaeo-acoustic study suggests that the ancients of the 3,000-year-old Andean ceremonial center at Chavín de Huántar, in the central highlands of Peru, practiced a fine art and science of manipulating sound with architecture to produce desired sensory effects. With the assistance of architectural form and placement, and sounds emitted from conch-shell trumpets, the “oracle” of Chavín de Huántar “spoke” to the ancient center’s listeners.

The buildings were constructed using a highly specialized combination of shafts, corridors and surfaces, all designed to make a series of echo chambers, in which sounds – often conch shell trumpets, called pututus, being blown by priests outside of the structure and chanting, as well as water running in streams under and around the buildings – would seem other-worldly. Add in the psychotropic effect of ritual consumption of San Pedro cactus juice (and possibly other substances, like ayahuasca), and one can easily see how a pilgrimage to such a temple would have been a profound spiritual experience.

Miriam Kolar, Stanford Inter-disciplinary Graduate Fellow, PhD Candidate at Stanford University and leader of the study says: ”At Chavín, we have discovered acoustic evidence for selective sound transmission between the site’s “Lanzon” monolith and the Circular Plaza: an architectural acoustic filter system that favors sound frequencies of the Chavín pututus (conch-shell trumpets) and human voice.

“The Lanzon is a sacred statue or stela depicting the central deity of the ancient Chavín culture. Thought to be Chavín’s central “oracle” for its inhabitants, it is housed in a chamber, part of a series of underground passages within the Old Temple of the ceremonial and religious center of Chavín de Huántar. A central duct was built to connect the area of the Lanzon monolith with that of the Circular Plaza, an open-air place of ceremonial activity and significance. The duct was specifically designed to filter and magnify or conduct to a certain sound range – namely, the special range emitted by the Chavín pututu instrument. The specific reasons for this acoustical configuration are not entirely understood, but studies involving human participants within the ancient architectural and artifact context of the site are indicating that the resultant sound effects may have been related to intentional auditory perceptual effects of sound and space on humans.

Acoustic resonance is a feature of many natural caves, and it’s likely that this natural feature was the primary motivator in the development of acoustics in ritual sites and practices. Modern technology allows archaeologists to identify and study such features of ancient sites, and in most cases the research is inaccessible to the amateur. However, there are branches of this endeavour that are within reach of anyone who can get themselves to the locations in question.

Recently, a team of researchers have been using sound to study the world famous Stonehenge megalithic site in Wiltshire, England.

According to experts from London’s Royal College of Art, Stonehenge holds more mystery than meets the eye. For many years, enthusiasts and researchers have held that Stonehenge had an audio component, either in its use or construction. Many visitors report that chants and music seem to resonate in a strange way at various points within and around the structure, but new insights seem to suggest that the stones themselves were musical instruments.

Research recently published in the Journal of Time & Mind, suggests that the bluestones – the smaller stones that make up the interior of the monument – actually have acoustical properties and may have been selected for that reason. It turns out that the stones resonate in a peculiar way when struck with a hammer or other instrument, and generate a wide range of sounds. Researchers even found what may be evidence of hammer or stone strikes on several of the stones, indicating that they’re on the right track.

English Heritage allowed archaeologists from Bournemouth and Bristol Universities to acoustically test the bluestones at Stonehenge, effectively playing them like a huge xylophone.

This research, with the input of other experts, suggests that many of the standing stone sites throughout the UK may have had, as a central feature, an acoustic nature. It may be that Stonehenge and other standing stone circles and like monuments were built as musical instruments, to be used in conjunction with or as a part of ritualistic gatherings and celebrations.

The same may be true for monuments all over the world, as is highlighted by researchers such as Michael Tellinger, who demonstrates in a video on his YouTube channel the acoustic properties of artifacts found at Waterval Boven, South Africa.

The “sonic rocks” could have been specifically picked because of their “acoustic energy” which means they can make a variety of noises ranging from metallic to wooden sounding, in a number of notes.

There is no denying it, sound has played a central role in the development of not only human spirituality and culture, but also in architecture. While most of our history can only be relayed in terms of visual artifacts and writing, the aural history of our ancestors just begs to be heard. And when you consider the fact that resonant sound has been a significant part of human life for upwards of 27,000 years (at least), it’s no wonder so many people feel so passionately about music and its makers.

So what does all of this mean? What explains these similar, yet geographically and culturally disparate finds?

“How curious that such varied ancient structures, separated by so much time and distance, should have common features which imply sophisticated knowledge”, observes Eneix. “Did the architects of the day each make and develop their own discoveries or did they inherit a concept from some older school of learning?

Scientists may never have the answer to that question, but the accumulating evidence suggests that there is a real story to tell about humans and their fascination with sound.

Additional Research:

As you may already know, Quartz, which consists of silicon dioxide, is the second most abundant mineral on earth. Quartz has amazing properties, some being these below:

- Pyroelectric – generates heat.

- Piezoelectric – generates electric charge when subjected to mechanical pressure.

- Can store data and information and is easily programmable – as evidenced by its rampant use in electronics and computers.

- Amplifies energy and has consistent energy output – has been used in “watches” for example.

Just like how we are using crystals today in natural formation and via manufactured variation, ancient civilizations have understood the value of crystal energy and have harnessed this energy for their advantage.